Graph RAG

Why Structure Beats Similarity

Traditional RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) has a dirty secret: it treats your knowledge like a bag of disconnected paragraphs. You embed chunks, find the most “similar” ones, and hope the AI can stitch together something coherent.

It works. Sort of. Until it doesn’t.

The problem shows up when you need context that isn’t semantically similar to your query—but is structurally essential to answering it.

The Limits of Vector Search

Avi Chawla’s visual explanation captures the problem perfectly:

Imagine you want to summarize a biography where each chapter covers a different accomplishment of a person. With naive RAG, you retrieve the top-k most similar chunks to your query. But summarization needs the full context—all the accomplishments, not just the ones that happen to match your embedding.

The chunks about “won Nobel Prize” and “founded company” and “wrote bestseller” aren’t semantically similar to each other. They’re about completely different topics. Vector search won’t naturally connect them.

But they’re all one hop away from the same person node in a graph.

This is the core insight: semantic similarity and structural relevance are different things. Vector search optimizes for the former. Many tasks require the latter.

Ask a standard RAG system: “What’s the authentication approach for the payment service?”

It dutifully finds chunks mentioning “authentication” and “payment.” But it misses:

The shared auth library that all services inherit from

The decision doc explaining why you chose OAuth over API keys

The architectural diagram showing the auth service’s relationship to payments

The three other services that use the same pattern (which would tell you this is established convention, not a one-off)

These aren’t similar in embedding space. They’re related in structure. And that distinction matters enormously.

Enter Graph RAG

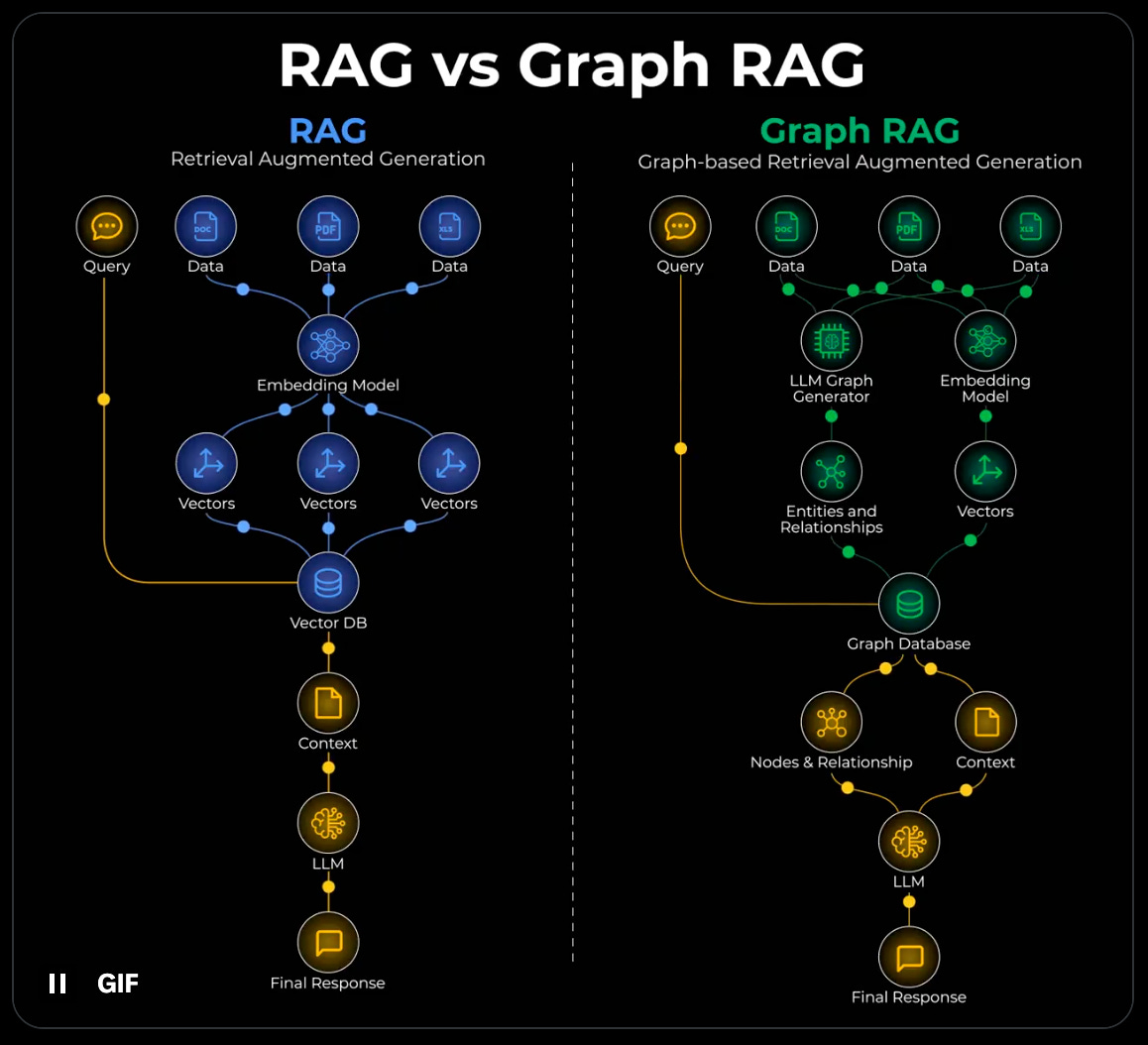

Graph RAG combines two retrieval mechanisms:

Vector search for semantic similarity (what sounds related)

Graph traversal for structural relationships (what actually connects)

The core idea, as Chawla illustrates:

Create a graph (entities & relationships) from your documents

During retrieval, traverse the graph to fetch connected context

Pass the structured context to the LLM

For the biography example: the system creates a subgraph where the person is a central node, and each accomplishment is one hop away. When you ask for a summary, graph traversal fetches all accomplishments—not just the semantically similar ones. The structure captures what vector search can’t.

The graph captures relationships that vectors can’t: “depends on,” “implements,” “decided by,” “supersedes,” “owned by.” When you query, the system retrieves not just similar content but connected context—the decisions that led here, the patterns this follows, the components this touches.

This is closer to how human experts think. When a senior engineer answers your authentication question, they’re not doing semantic search in their head. They’re traversing a mental graph: “Payment service... that uses our standard auth pattern... which we chose because of the X decision... and it’s similar to how we did it in the Y service...”

Why This Changes Code Understanding

Codebases are graphs. Files import other files. Functions call functions. Classes inherit from classes. Decisions cascade through architectures. Developers learn from past patterns.

Vector search flattens all of this into a soup of embeddings. Graph RAG preserves the structure.

Consider what you can answer with proper graph traversal:

“What would break if I changed this function?” → Follow the dependency graph

“Why did we build it this way?” → Traverse to the decision docs and discussions

“Where else do we use this pattern?” → Find structurally similar implementations

“Who knows about this area?” → Track ownership and contribution relationships

None of these are semantic similarity questions. They’re structural queries that require understanding relationships.

Claude-MPM: Graph RAG in Practice

I’ve been using claude-mpm for agentic development, and it implements exactly this pattern. The architecture combines:

Kuzu — A graph database that stores project-specific knowledge graphs. Not just facts, but relationships: which files relate to which decisions, which patterns connect to which implementations, which architectural choices cascade to which components. The graph persists across sessions, so agents build cumulative understanding of your codebase.

MCP Vector Search — Semantic search over your code using embeddings. Find code by intent (”authentication logic”) not just keywords. This handles the similarity dimension.

The combination — When an agent needs context, it’s not just grabbing the most similar chunks. It’s traversing relationships: “This file implements that pattern, which was decided in this doc, and relates to these three other services.” The retrieval is structurally aware.

The result: agents that actually understand your codebase’s architecture rather than just pattern-matching against text.

The Context Quality Problem

Here’s the insight that makes Graph RAG essential for AI-assisted development: context quality determines output quality.

Feed an AI the wrong context and it confidently produces wrong answers. Feed it incomplete context and it hallucinates the gaps. The difference between helpful AI and frustrating AI often isn’t model capability—it’s retrieval quality.

Graph RAG attacks this directly:

Relevant context — Graph relationships filter for what actually matters, not just what sounds similar

Complete context — Traversal brings in structurally connected information that vector search would miss

Prioritized context — Relationship types help rank what’s most important (direct dependency > distant reference)

When your agents have better context, they produce better code. It’s that simple. And that hard to achieve with vectors alone.

Building Your Graph

The graph doesn’t build itself. You need to capture relationships as they form:

Structural relationships — Parse imports, dependencies, inheritance, API contracts. These are deterministic and should be automated.

Decision relationships — Link implementations to the decisions that shaped them. This requires discipline (or tooling like TkDD that captures decisions in tickets and connects them to code).

Pattern relationships — Identify similar implementations and connect them. Partly automated through code analysis, partly human curation.

Ownership relationships — Track who built what, who reviewed what, who owns what areas. Inferred from git history and organizational structure.

The initial investment pays compounding returns. Every relationship you capture makes future retrieval more precise.

The Ontology Layer

Graph RAG gets even more powerful when you add an ontology—a schema that defines what types of nodes and relationships exist in your domain.

For a codebase, your ontology might include:

Node types: Service, Function, Decision, Pattern, Team, Document

Relationship types: implements, depends_on, decided_by, owned_by, similar_to

The ontology does two things:

Constrains the graph — You can’t have nonsense relationships like “Function implements Team”

Enables typed queries — “Find all services that depend on auth AND were decided by an architectural decision record”

This is the difference between a pile of connected nodes and a structured knowledge system.

Where This Is Going

The future of AI-assisted development isn’t better models—it’s better context. Models are already capable enough. What limits them is our ability to provide the right information at the right time.

Graph RAG is part of that answer. Vector search alone isn’t sufficient for understanding structured domains like code. You need both similarity and structure.

The tools are maturing. Kuzu, Neo4j, and other graph databases are getting easier to integrate. Vector databases are becoming commoditized. The combination—Graph RAG—is becoming a recognizable pattern.

If you’re building AI-assisted development tools or workflows, this is worth understanding. The teams that get context right will ship circles around teams that don’t.

I’m building an AI-first development workflow that combines dual track agile, TkDD (Ticket-Driven Development), and tools like claude-mpm. More on that in future posts.